FROM BIOTECH TO PI DAY:

Mill Valley Scientists

BY POTTER WICKWARE

PUBLISHED IN 2023 Mill Valley Historical Society Review

In the sea change that swept the country after World War II some of the best minds ended up in Mill Valley. They helped create the new field of biotechnology, eradicate smallpox, track and predict volcanos, protect the coast and open space, and even establish the Exploratorium and Pi Day.

In his pivotal book Science, the Endless Frontier, Truman-era Presidential Science Adviser Vannevar Bush proposed initiatives that led to the creation of the National Science Foundation, NASA, and a greatly expanded health research establishment, the National Institutes of Health. With important outposts in the Bay Area these agencies accelerated a population shift from east to west that was already underway before the war. Local scientists were caught up not just in their fields but in the spirit of the time and place and were involved beyond science with their interests in government, business, media, philanthropy, the environment and, of course, local music.

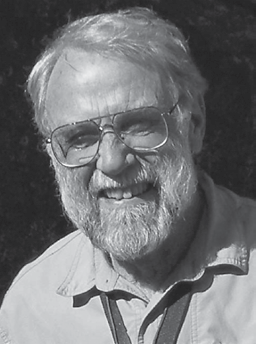

Exploratorium wizard Larry Shaw in front of the Exploratorium at Pier 15 in San Francisco on Pi Day, March 14, 2014. Courtesy of Catherine Shaw.

THE CUTTING-EDGE BIOLOGISTS

Henry Bourne, retired chair of pharmacology at UC San Francisco, a longtime Mill Valleyan (now of Corte Madera) who came to the Bay Area from the NIH in Washington in 1968, recalls, “The East Coast was a place of grand old men and hard-to-budge traditions back then. But there was a big change in biology going on, and in science overall, and it was centered here in northern California. I had once naively thought that science was copying from other people, and when I found out it’s not, it was an absolute thrill to know that you don’t have to memorize and follow some theory, but instead can control and manipulate your own problem and ask all sorts of what-if questions.”

During his tenure from 1959 to 1967, Governor Pat Brown was building canals and highways and adding campuses to the University of California, a public, state-supported university that enrolled a flood of mature and motivated GI Bill students. “Clark Kerr as president of UC was a visionary public figure, and under him UC became one of the world’s great universities. It was just spectacular. And northern California was just the right place for it. People used to say there must be something in the water out here,” Bourne says. “And in those days it was affordable!”

UC San Francisco, where the biotech revolution began unfolding in the late 1960s, was at the time transitioning clinical studies from Berkeley to the new campus in San Francisco. Sausalitan Sam Barondes, now retired chair of psychiatry at UCSF and former director of the Langley Porter Institute, says “in those days UCSF was a rather ordinary medical school,” one of about 200 in North America, “and to think it was going to become the world leader, the place where biotechnology was to be invented, was a far-fetched idea. It could have happened at other places, like MIT, for example, but UCSF was the institution that was really setting the pace. All through the 1970s they had brilliant recruiters going around finding the smartest young people they could find and bringing them in. San Francisco was incredible; it was my favorite city, and I moved my family up to southern Marin from San Diego. I loved it here.”

Creativity and invention took root and flowered. The collection of techniques known as genetic engineering is an example. In the early ’70s the Mill Valleyan (now southern Californian) UCSF postdoc Herb Boyer was pondering the failure of conjugative strains of the bacteria E. coli to properly transmit inserted sequences. An equally esoteric question was bothering the new Stanford faculty member Stan Cohen: the role of the cellular elements known as plasmids in antibiotic resistance. Boyer supposed it might have something to do with the recently discovered enzymes called restriction endonucleases. When the two scientists met at a conference in Honolulu and compared their work, they realized that with techniques they had devised, which came to be known as recombinant DNA, they had discovered what they had not been looking for. Among the first applications that made it out of the lab and into the world was synthetic human growth hormone, which formerly had been extracted from cadavers and used to treat dwarfism, and the core metabolic regulating hormone insulin, which used to come from swine. In the earlier era these products brought to human patients, along with their healing properties, a burden of viruses and other infectious agents. Eliminating this lethal hazard via recombinant technology led to the industry that came to be known as biotechnology. Boyer and Cohen linked up with the venture capitalist Robert Swanson to found Genentech, their start-up company, which is today an enterprise with over $26 billion in annual revenue and 14,000 employees, joined by hundreds of other such companies worldwide.

Henry Bourne, retired chair of pharmacology at UC San Francisco, in February 2023. Photo by Potter Wickware.

Molecular biologist Gordon Tomkins in 1968 with his wife Millicent and their daughters Tanya (left) and Leslie in Chevy Chase, Maryland. They moved to Mill Valley in 1969. Courtesy of Tanya Tomkins.

The metamorphosis of UCSF from also-ran to world leader stemmed in part from the efforts of Holly Smith, dean of medicine, who arrived from Harvard in 1964. To revitalize a sclerotic biochemistry department he recruited Bill Rutter and Gordon Tomkins to build a new department of biochemistry and biophysics. Tomkins, who moved to Mill Valley from the NIH in 1969, joined Rutter, from the University of Washington, as vice chair and together they began to recruit key researchers who laid the foundation for a new kind of academic medicine that merged multidisciplinary practice with basic research science.

Tomkins, recalls Barondes, “was this kind of magical person, like a Pied Piper. He got things right away. He was very generous, and you could come talk to him anytime, not only about science. He had some great ideas. He understood everything. When the Journal of Biological Chemistry came, a big thick journal, he grabbed it and took it home and read the whole thing, and the next day he knew everything in it. Back then the double helix was still a new thing and people didn’t even use the word molecular to talk about biology. Gordon Tomkins was the only person in the world at that time I think who understood conceptually the shift that was happening. He conceived that the way hormones worked was by regulation of gene expression. I myself didn’t know what this meant because the work hadn’t been done and vetted yet.”

R. L. Bernstein, retired professor of biology at San Francisco State who’d been a postdoc in Tomkins’ lab at UCSF, recalls that Tomkins, who did fundamental labor working out the steps of gene expression, “was not a physically dominating presence, not a prepossessing-looking man, but somehow when he entered the room everyone immediately recognized how intelligent and competent he was, and all attention focused on him. He radiated a kind of power, was full of energy, curiosity, and ideas and if he thought you were of like mind he immediately bonded with you. He was fantastically capable in a lot of different areas.”

Tomkins’ daughter, the cellist Tanya Tomkins, recalls big gatherings of scientists, writers, and artists at the family home on Eugene Street in Mill Valley: biochemists Bruce and Giovanna Ames, writers George Leonard and Mike Murphy of the Esalen Institute, and many others. Tomkins had played sax with Stan Kenton’s band (he also played flute, clarinet, and piano) and musicians gravitated to him, Bernstein recalls. “People would come to the lab and talk about music for hours. He spoke several languages; the French postdocs in our lab said he had a perfect Parisian accent. He’d worked at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, had been a chief resident at Harvard—not an easy post for an MD to attain—in addition to his PhD from Berkeley. It was a tragic loss to science and the community when he died at 49, due to a medical error.”

THE RADICAL EPIDEMIOLOGIST

Longtime Mill Valley resident Dr. Larry Brilliant, formerly an epidemiologist with the World Health Organization and on the team that stamped out the last remnants of smallpox in India in the 1970s, a founder of the early internet portal The Well, and former director of Google and other companies, and now a CNN medical analyst, recalls looking for a summer job when he was in medical school in Michigan.

“The job I found was civil rights specialist for the U.S. gov- ernment. It was 1967, the Civil Rights Act had just been passed and Lyndon Johnson had created a new agency, the Office of Equal Health Opportunity. Many hospitals were still segregated in those days and our job was to inspect them for discrimination, mostly against African Americans. I was sent to Mississippi with another medical student from Utah. Part of our job was to sneak into the hospitals when no one was looking, mostly at night, and see if they were hiding their Black patients or treating them badly. It was noble work; I had marched with Martin Luther King and was part of the civil rights movement.”

But being a civil rights specialist in Mississippi in 1967 was not a comfortable occupation. “The hospital administrators down there hated us. There was an incident where gunshots were fired, and I discovered that the other medical student had brought a gun with him and shot back. We were evacuated and I was reassigned to, of all places, San Francisco. I was brought out in a federal aircraft into Crissy Field. It was the middle of the Summer of Love. I had no way to resist the temptations of San Francisco, and it was a life-changing experience for me. I met David Crosby and Jerry Garcia and became lifelong friends with Wavy Gravy, and hung out in the Haight-Ashbury, and smoked dope, and oh, the girls! It was the most wonderful time of my life.

“As a civil rights specialist I had some authority and I also got important work done. In San Francisco, I remember going into the old Southern Pacific Railroad Hospital on Fell Street. Railroad work injuries were notorious back then and the standard of care needed to change. I was 23 years old and I was telling the head of Southern Pacific, ‘I’m gonna close you down!’

“I went back to Michigan and finished medical school and returned to San Francisco in 1969. I tried to get an internship at San Francisco General, but every other radical doctor in America had the same idea, so I ended up at Presbyterian Hospital, which was the hospital of the rich and famous. They’d never had an internship class like us. They selected us because of our academic records but they didn’t know anything about the culture we’d absorbed. I’d go out and march against the war in Vietnam and some of the older doctors would say I should be fired. When the Indians took over Alcatraz I went to the island and delivered a baby there, and when I came back some of the doctors thought I should be fired for that too.

“How I got to Mill Valley was I was doing my internship at Presbyterian and one of the attending physicians went on a month holiday to Italy. He was Italian and he asked me if my wife and I would like to house-sit for a month, so we house-sat. It was a big act of bravery for him to let a couple of hippies live in his house for a month. We were in the middle of the redwoods. It was magnificent. Girija and I’d go down to the Depot for coffee and breakfast. What a scene! People were so kind, and everybody seemed so smart and there was great music and I loved it.” After Alcatraz, Brilliant spent a few years at an ashram in India, “but I always wanted to come back to Mill Valley because there’s no other place like it.” After India he did come back and has been here ever since.

There is a downside, he acknowledges. “It’s gotten so damned expensive. Back then rents were lower here than in New York and Chicago and many other places. There were these large old mansions in Pacific Heights that had been abandoned by their owners and you could rent a huge mansion on Broadway and have 20 or 30 young people sharing the place with you.

“Today it’s changed a lot. You don’t have as many hot tubs and hippies, and they’re not gonna film Serial here, and yes, it’s become more elite, with more bankers and hedge fund capitalists moving in. But what has not changed is that people here have a high consciousness and a tremendous amount of compassion, are interested in the world, and care deeply about the poorest and most vulnerable people. The conversations you have with people here in Mill Valley! They’re wonderful conversations; ‘give me mine and I want more’ are not what you hear, not what you talk about when you’re having a cup of coffee at Equator or lunch at D’Angelo’s.”

Dr. Larry Brilliant (left) with Wavy Gravy and Ram Dass (seated), three founders of Seva Foundation, an international nonprofit health organization based in Berkeley, specializing in the prevention and treatment of blindness and other visual impairments. Courtesy of Dr. Larry Brilliant.

THE VOLCANOLOGIST

People sometimes feel that scientific topics can be a little boring and off-putting. The cryptic vocabulary, the bureaucratic com- plexity of big grants with their lengthy time frames—especially in this time of institutional big science—can make science seem dismaying. But the essence of the work, going back to the time of Archimedes and before, can be reduced to a simple formula: observe, understand, explain.

Volcanologist Wes Hildreth, senior scientist with the U.S. Geologic Survey at its regional center in Menlo Park, who grew up in Mill Valley, graduated from Tamalpais High, and got his degrees from Harvard and UC Berkeley, sees a bare simplicity in the work he does.

“I’m kind of a classic naturalist, interested in outdoor geology and understanding the stratigraphy and lithology of the folded rock of Marin County and Mill Valley. What was nice about Mill Valley was they left you alone and let you figure things out on your own. I spent a lot of time hiking in the Coast Range and the Sierras and in the Cascades wilderness with Mill Valley girl Nancy Williams, looking at the rocks and listening to what they have to say. There’s a lot of interesting geology here in Marin. I was a lover of granite long before I was a lover of volcanos. My model, in some ways, was John Muir. A lot of what I learned was before I went to graduate school.

“My interest in volcanology started in February of 1943, when I was not yet five years old, with the eruption of Parícutin in Mexico. It made the headlines of the Boston newspapers, and I was just on the edge of learning to read. It was the first time I ever read a newspaper. And when I first flew out of the United States to Europe the summer after I graduated from college,we flew over a volcano island off the coast of Iceland which was actively erupting. The pilot of this Icelandair plane actually swung right down over the crater and the passengers on this ordinary commercial flight got a close look at the eruption going on down there off the south coast of Iceland.”

Travels after college took Hildreth in a VW bus down to Mexico where he had a closer look at Parícutin, then to Central America back when Somoza was expelled from Nicaragua and Ortega came in. Then down to Chile and up to Alaska in the Katmai Range.

“I was at Mount St. Helens in 1980. There had been a month and a half of intermittent seismic and to a lesser degree steam magma activity and other hotspot stuff in the crater. I’d worked the previous summer at Katmai and had been out to Augustine Island, which had erupted in 1976. That had been the basis of Dave Johnston’s PhD thesis; and Dave and I were very tuned in, in a premonitory way to the things that lead to eruptions, so when the activity started in late March at St. Helens, Dave and I went up there. We had several days and lookout points on opposite sides of the volcano and observed. We took a plane flight to have a close look at the crater and I was scared to death because there was fog and you couldn’t see and neither could the pilot, but we made it. After that I went back to Menlo Park. But Dave stayed and he was killed by the main eruption when it happened on May 18. Then a lot of USGS and other academic people came up and swarmed around, and it led to the establishment of the Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Washington, where they try to anticipate natural processes and prevent them from becoming natural disasters.

“I work closely with seismologists and other geophysicists who are basically in front of their computers. But the field work I do defines the product that gets published and studied. I work out the eruptive history of the volcano and do a lot of dating on different eruptive units in order to establish how long and how often the volcano’s been erupting, whereas the other people are in committees and chasing grant money.”

Volcanologist Wes Hildreth at Devils Postpile National Monument in June 2022, explaining to a party of National Park Service interpreters the cooling process of the 80,000-year-old basaltic lava flow. The “pile of posts” has accumulated since the last deglaciation (16,000 years ago), falling from the cliff one earthquake at a time. Photo by Fred Murphy.

Wes Hildreth. Courtesy of USGS.

THE BOTANIST

With degrees from Mt. Holyoke College (zoology) and Yale (biochemistry), botanist and activist Phyllis Faber was another transplant from the East Coast who joined the throng moving to northern California in the 1970s. In Marin County, Faber, who died January 15, 2023 at age 95, found a rich flora in a diverse county in a very diverse state. “We’ve got a great diversity of wetlands,” says botanical illustrator Kristin Jakob, Faber’s friend and colleague in the California Native Plant Society. “Marshes to streams to seasonal ponds, and freshwater and saltwater marshes abound in the coastal land along the bay, so she had a lot of material to work with here. The nature she found here after her move just inspired her.”

Faber’s interest in marsh plants, both freshwater and saltwater, led to her involvement with the California Coastal Commission, which grew out of the Proposition 20 citizen initiative of 1972 to regulate development along the coast and prevent the kind of runaway development that occurred in Santa Clara County and other heavily populated areas of the state. She was alarmed by uncontrolled growth in those years of proliferating freeways, harbor districts and marinas, bay and ocean sewage outfalls, and master plans that only presaged more uncontrolled development stretching into the future.

After passage of Prop. 20, former State Senator and Mill Valley City Councilman Peter Behr appointed her to the regional Coastal Commission, where she served from 1973 to 1979. She also served for many years as chair of the advisory committee to the signature natural areas program of the California Department of Fish and Game and was a cofounder of the Marin Agricultural Land Trust, in 1980 joining Ellen Straus—a botanist and a rancher—and local ranchers and conservationists in the goal to protect family farms from mounting development pressure. Today more than 55,000 acres in Marin County have been safeguarded, and more than $1.8 million invested in projects that improve soil health, protect water quality, and increase grassland vigor. A prolific writer and publisher, Phyllis Faber received a Milley Award for Literary Arts in 2004.

Botanist and Marin Agricultural Land Trust cofounder Phyllis Faber at the Gale Ranch in Chileno Valley, 2012. Photo by Lou Weinert, courtesy of MALT.

Alice Eastwood, Botanist

Eastwood Trail, Camp Eastwood, and Camp Eastwood Road are on Mt. Tamalpais maps. Eastwood Way and Eastwood Park are in Tam Valley. They are named for the self-taught botanist Alice Eastwood, who botanized Mt. Tam actively from 1912 to 1929. She was the curator of botany at the California Academy of Sciences from 1892 to 1949. Born in Toronto in 1859, she died in 1953 at age 94 in San Francisco.

In 1920, she built a house at what is today 609 Summit Avenue in Mill Valley. Her three- acre garden was a botanical museum. After using the place on weekends, she rented it out for several years. It was destroyed in the 1929 fire. In 1912, she became a charter member of the Tamalpais Conservation Club. She was also one of the few women permitted, by reason of her hiking prowess, to become a member (but only as an associate) of the all-male Cross Country Boys Club. She and a few of her club friends were known as the “Hill Tribe.” A member described her as “a famous plant-hunter who trudged easily twenty miles a day carrying her heavy plant presses on her back.”

– Chuck Oldenburg, from Mill Valley Vignettes

THE SCIENCE WIZARD

People might think that the language of science is daunting, the ideas abstruse, the equipment too intricate and specialized for normal people to use, but Mill Valleyan Larry Shaw would laugh these objections off: Science is interesting! Science is fun! he proclaimed. He had been a physicist at both Lawrence Livermore Lab and UC Berkeley when he was recruited by Frank Oppenheimer in 1972 to help build the Exploratorium, the new “science for the people” museum initially located at the Palace of Fine Arts (now at Pier 15) in San Francisco. Shaw’s widow Catherine explains that her husband was a practical Thomas Edison type, good with his hands, who helped artists and other presenters with technical issues getting their displays up and keeping them running.

In 1988, Shaw noted that the date March 14 in month-day format corresponds to the famous irrational transcendental number π, which has fascinated mathematical people eversince the ancients began using geometry for practical purposes. (Some people have tried to discern a repetitive pattern, or any pattern at all, in the endless flow of numbers to the right of the pi decimal point, and some are still trying, but they have never succeeded. At least not yet.) Because March 14 is also Einstein’s birthday, the date is mathematically doubly important, and Shaw and his colleagues began observing it annually. The celebration starts at 1:59 p.m. (which when combined with the calendar date makes 3.14159) and consists of people marching around a circular space at the Exploratorium 3.14 times, eating pizza and fruit pies, wearing pi-themed attire, and reading books and watching films that have π in the plot. The tradition caught on and continued, and in 2009 the U.S. House of Representatives passed a nonbinding resolution certifying March 14 as Pi Day, making it a designated U.S. national holiday.

Shaw was a follower of Buddhism, an appropriate belief system for scientists, Catherine explains, because it does not have a doxology that prescribes what you have to believe.

Larry added art to the traditional STEM curriculum, so now at the Exploratorium there is STEAM: science, technology, art, engineering, mathematics. The Exploratorium’s focus has extended beyond science to human perception more generally and aims to show that these activities and experiences can help us understand how the world is made, meet its challenges, and have some fun while doing so.